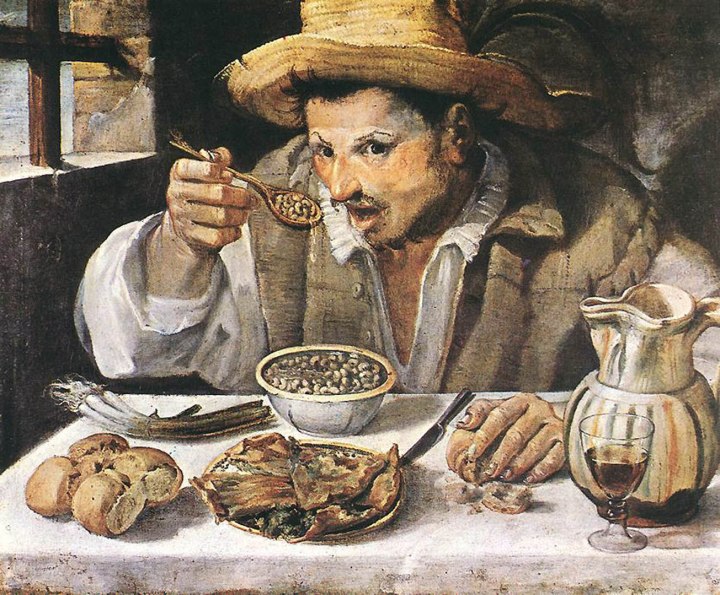

Annibale Carracci’s Bean Eater (ca. 1584) is a portrait of a man frozen in time. We have interrupted his meal in mid-bite; he looks either startled or suspicious, and most commentators find him to be a rude fellow, one who “greedily scoops” a bowl of beans with “loud table manners” (whatever that means), casting an unwelcoming scowl at the viewer. For art historians, Carracci’s rough brushwork and earth-toned palette mark the man as a coarse peasant; that he sits by a window with crumbling plaster further marks him as uncouth.

I beg to disagree. While he is undoubtedly a manual laborer, given his sun-tanned complexion, he is neither crude nor vulgar, and we should be careful not to read our contemporary standards onto this 16th century man. His frayed hat and simple, vegetarian meal suggest frugality, although the meal could just as easily indicate a fast day in Catholic Italy. The raw onions confirm his peasant stock: dietary advice of the day held that those who worked the land were best suited to foods from under or close to the earth’s surface, such as beans, roots, and bulbs.

Even though a peasant, the bean eater is not a poor man, and he dines politely according to 16th century table manners. His shirt is clean and his tablewares modest, but fashionable. His table is laid with a white cloth, and he drinks from a stemmed wine glass, quite likely the simplest blown Venetian wares, rather than from a cheaper earthenware or wooden cup. His tricolor wine jug is maiolica, highly fashionable, if vernacular, in the 15th and 16th centuries. His knife is clearly for the table, rather than an all-purpose cutter that so many paintings of the era show, and his bean bowl and plate holding the vegetable torta seem unchipped. Even his bread appears to be a light wheat loaf, perhaps not the finest white manchet, but certainly not the heavy black breads of the poorest sort. But most important is his bodily comportment: his spoon may be wooden and fairly large, but it is appropriately proportioned for table use, much like modern, capacious soup spoons; it is not a kitchen tool. He holds it gracefully between two fingers, rather than clutching it in his palm.

Even his bread appears to be a light wheat loaf, perhaps not the finest white manchet, but certainly not the heavy black breads of the poorest sort. But most important is his bodily comportment: his spoon may be wooden and fairly large, but it is appropriately proportioned for table use, much like modern, capacious soup spoons; it is not a kitchen tool. He holds it gracefully between two fingers, rather than clutching it in his palm.

We compare The Bean Eater against Vincenzo Campi’s The Cheese Eaters (ca. 1580), where three leering men are gorging themselves on a mound of fresh ricotta (another food suited to the lower classes) with a woman of questionable virtue. The red-capped man uses a kitchen spoon to cram cheese into his mouth; it looks as if some is about to fall out. He clasps the spoon in his fist, as if a weapon, and greedily hunches over the table. Behind him, another is about to try to insert a heaping pile into his mouth at a very awkward angle, holding the spoon with all five fingers; even if the cheese does not slip from the tilted bowl, he will have difficulty taking it all in.

Painters were well-aware that their depiction of their subject’s gestures could communicate manners. The Groot Schilderboek, a Dutch painter’s manual from 1707, tells the artist to communicate differences in social class by the manner in which his subjects hold wine glasses. Aristocrats know to hold glasses by the foot, while those lower on the refinement scale will fondle the stem or grasp the bowl. In Campi’s painting, the characters are stuffing themselves as opportunity presents. They make no pretense to the restraint that table manners impose: no table clothed in white, no chairs, no drinks, no bread, hands reaching into the single dish helter-skelter. They personify warnings in Giovanni Della Casa’s 1558 etiquette manual, Galateo, that

Painters were well-aware that their depiction of their subject’s gestures could communicate manners. The Groot Schilderboek, a Dutch painter’s manual from 1707, tells the artist to communicate differences in social class by the manner in which his subjects hold wine glasses. Aristocrats know to hold glasses by the foot, while those lower on the refinement scale will fondle the stem or grasp the bowl. In Campi’s painting, the characters are stuffing themselves as opportunity presents. They make no pretense to the restraint that table manners impose: no table clothed in white, no chairs, no drinks, no bread, hands reaching into the single dish helter-skelter. They personify warnings in Giovanni Della Casa’s 1558 etiquette manual, Galateo, that

It is rude fashion, besides, to leane over the table, or to fill your mouth so ful of meate, that your cheeks be blowne up with all.

Although humble, Carracci’s Bean Eater displays none of the failings identified by Della Casa. The artist portrays his subject sympathetically, naturally, without romanticization. The Bean Eater is neither rude nor greedy, sitting privately behind his table, inclining his head just a bit to eat his pottage. It is we, the viewers, who have rudely intruded upon his solitary meal. If, in that moment of surprise, a bit of liquid drips from his bean pottage to soil his tablecloth, then we are to blame. And if the cloth is soiled, everything in the painting suggests that it will be freshly laundered before the next meal.