The fork’s journey to the table as a ‘civilized’ dining tool is fraught with politics, religion, snobbery, and a whiff of salaciousness. Forks are not needed to dine neatly: indeed, food falls from forks more frequently than from fingers. Different cultures have devised different table etiquettes to fit with their preferred tools, and different cuisines privilege fingers, chopsticks, or forks. But nearly every culture has devised fork-like tools for cooking. The efficiency of the large pronged tools in handling so many kitchen tasks, from fishing out morsels in a cauldron to roasting items over a fire, to steadying a large joint for carving, might have made their acceptance at the table seem easy and natural. Yet forks failed to become part of the standard Western couvert for more than 1,500 years after the first table forks were used in the Roman world, and even in seventeenth-century England, fork aficionados were mocked. Why?

Small, table-sized forks have been found as grave goods in archaeological digs in China that date back more than 4,000 years. Explicitly religious uses of forks start in the West in the ancient Egyptian Book of Thoth, where a “forked stick in hand and a fire-pan” are required for a sacrifice. The Old Testament’s Book of Samuel (Book 1, 2:13-14) describes the right of priests at sacrifices to send a servant with a three-pronged fork to “thrust it into the pan; . . . all that the fork brought up the priest would take for himself.” So, too, the Odyssey describes sacrificial meals where men hold five-prong forks spitted with fat and meat. But it is not until the Middle Ages that we have literary evidence of the use of dining forks in secular settings.

The conventional story holds that the fork was introduced into Venice during the late 10th or early 11th century by a Byzantine princess sent to marry a doge’s son. The purpose was political: cement an important alliance. The princess, undiplomatically, shocked the Venetians (so the story goes) by eating from a delicate gold fork. Especially vocal in his culture wars was the ascetic Peter Damian, the Bishop of Ostia, who called her conduct an affront to God for forsaking her natural fingers in favor of this instrument of the Devil. That forks evoked visions of a miniaturized pitchfork made his outrage seem all the more compelling when the princess soon died an agonizing death from a plague. In Damian’s words, it was God “blandishing the sword of justice” for her arrogance and vanity.

Yet writing in the year 1007, Damian’s fiery rhetoric may have been more temporal than spiritual: the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Churches were battling for political and doctrinal supremacy. Venice walked a fine–some might suggest duplicitous–line between the Churches, acting as an entrepôt for the riches of the East while professing (usually) fealty to Rome. From Rome’s perspective, alliances that brought Venice closer to Constantinople were a potential threat, hence Damian’s dismay at the marriage and his eagerness to tar the princess with blasphemy.

Less opinionated references to forks or fork-like tools peek out amidst the records of the three hundred years following the princess’s demise: two well-dressed gentlemen dine from forks in this illustration from the Rabanus Maurus Glossaria, dated to 1023 and produced at the Abbey of Montecassino, in central Italy.

Traveling through the area that is now the Ukraine, just north of the borders of the Byzantine Empire, the monk William of Rubruck encountered Mongol nomads who ate minced mutton from the “point of a knife or a fork, which they make for the purpose, like that which we use to eat coddled pears.” Inventories document the solo forks as kingly possessions, including a gold fork owned by Louis d’Anjou in 1368, possibly given to him by Byzantine Cypriot diplomats at the Convention of Kraków in 1364. At the same time, Catalans, thought by some to possess Europe’s more sophisticated manners, were using a broca, a small pronged spear, at table, while the King of Naples likely used a wooden punteruolo, also a small spear capable of piercing food and conveying it to the mouth: a cookery manuscript in his library asserts that a punteruolo is essential for eating pasta, which, like white bread, was a relative luxury in the 14th century.

Etiquette books begin discussing dining forks no later than 1560, when Calviac’s Civilité notes different customs and utensils among the French, German, and Italians when eating ragouts. Forks are illustrated in the Bartolomeo Scappi’s massive cookbook and guide to the organization of great feasts, Opera (1570); it is unclear from the woodcuts whether these forks are meant for the kitchen or table. Henri III, notoriously regarded as unbecomingly effeminate, used dining forks, as did his equally critiqued courtiers; his death by assassination seemed to many a fitting end. A century later, Louis XIV refused to use a fork and forbade his children to use one, notwithstanding the efforts of their tutor and the shifting mores. With Louis’s notable exception, nearly everyone in the European upper classes of the eighteenth century would wield a fork at table.

Most baffling, however, is the appearance, and equally mysterious disappearance, of tools that functioned like a fork, spearing tidbits and transporting them to the mouth. The cochleare was a spoon with a handle that ended in a pointed tip to extract snails (a favorite Roman delicacy) from their shells, as these third century examples show. And, curiously, medieval spoons typically had blunted finials, making it impossible to use them to pierce foods.

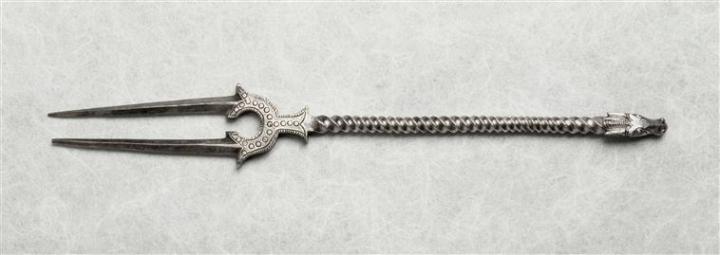

Even more remarkable is the Roman equivalent of a Swiss Army knife that does the modern version one better with its fork and removable toothpick. Also dating to the third century, this multifunctional silver tool is thought to have belonged to a wealthy traveler, perhaps a merchant. An ingenious tool, although a bit awkward and off-balance to use.

But the most elegant of Roman utensils is a lovely third century gold and silver fork and spoon housed at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, impeccably balanced, its form follows its function. Adorned with a panther, a symbol of Dionysius, the god of wine, can there be little doubt why killjoys like Peter Damian bellowed that forks were an offense to his God?