We have all read stories about contemporary wine fraudsters who pour new-ish wine into very old bottles and cleverly send them at auction, reaping vastly inflated prices. Few of us sympathize with the well-heeled oenophiles who fall prey to the scams. They seem pretentious fools and vulgarians, sheep waiting to be fleeced.

Wine scams are nothing new, nor are their victims any more likable when looking at the role of wine, hospitality, and connoisseurship in the ancient Roman world.

Wine scams are nothing new, nor are their victims any more likable when looking at the role of wine, hospitality, and connoisseurship in the ancient Roman world.

Petronius’s Satyricon is sometimes called the world’s first novel. Written in the first century CE, its most famous chapter, Trimalchio’s Feast, lambasts the ostentatious party world of Rome’s ruling elite, a group for whom conspicuous consumption was the order of the day. Petronius was the Emperor Nero’s arbiter elegantiae, his life-style consultant, responsible for producing the garishly lavish parties for which Nero was infamous. On Nero’s orders, Petronius committed suicide after being pilloried with trumped-up charges of treason, but not before he could make sure his insider’s satire of Nero’s reign would find an audience.

Trimalchio’s Feast tells the story of an all-night dinner party from the perspective of a guest who is unfamiliar with his host, but learns more than he bargained for over the course of the evening. Trimalchio is a freed slave who has made tons of money in business and can’t wait to flaunt it. His jewelry is gaudy, his napkins edged with imperial purple, and his farts are loud, smelly, and unabashed. As the evening progresses, Trimalchio boorishly tells his guests to drink up, as he is honoring them with finer wine than he had served the night before to social betters.

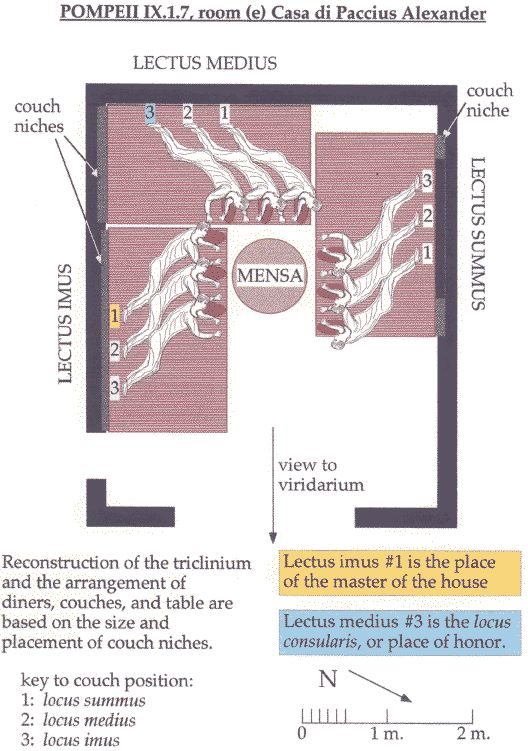

Trimalchio’s boast offers a peek into Rome’s social hierarchies of the first century CE. Like most societies descended from aristocracies, historic bloodlines mattered far more than wealth, so for all of Trimalchio’s riches, he will never be more than nouveau riche. Social standing was constantly reinforced at dinner parties, Rome’s preeminent form of private entertainment. Taking place in the triclinium, the “Room of Three Couches,” each couch was coded with status: everyone knew where everyone else ranked by which spot on the couch they were given. The host and family members, with self-deprecating hospitality, occupied the lowest couch (lectus imus), the guest of honor reclined immediately adjacent to the host on the lectus medius, while the diners on the aptly-named lectus summus were the second, third, and fourth most important guests.

In addition to one’s berth in the triclinium, food and drink could visibly divide guests. Pliny the Younger (Epistle 2.6) and Martial (Epigram 4.85.1-2) criticized hosts who, whether due to expense or the desire to humiliate a guest, instructed slaves to serve certain guests inferior items. Subtler hosts might use opaque glassware or silver cups to disguise the appearance of different wines, favoring the chosen few with the finest wines while offering plonk to others, all while appearing egalitarian.

But Trimalchio seems a generous, if buffoonish, host. The wine he serves this particular night is labeled “Falernian of Opimius’s Vintage, 100 Years in the Bottle.” As I have detailed elsewhere, Falernian wine, made from grapes grown in Campania just south Naples, was among the most esteemed wines of the ancient world, the Haut Brion of its day, and the particular vintage was thought especially fine. There is just one problem with Trimalchio’s boast: the timing strains credulity, or at least drinkability. Roman vintages were dated by the name of the consulate in office; Opimius was consul in 121 BCE. Trimalchio’s Feast takes place in about 60 CE, thus making the wine 180 years old. Moreover, the wine label claimed that its contents were “100 Years in the Bottle,” meaning it was bottled around the year 40 BCE. If so, that wine would have been one of the first wines ever to have been stored in a glass bottle, as glass blowing, the technology needed to make bottles of a size appropriate for storing wine, was invented at around that time in the ancient Near East. Had Trimalchio known his wines, his vintages,or a little bit about the technologies of the past 100 years, he might have realized something was amiss. Instead, like modern wine snobs, he was likely duped.

Triclinium diagram from Dr. Pedar Foss, “Kitchens and Dining Rooms at Pompeii: the spatial and social relationship of cooking to eating in the Roman household,” Ph.D. thesis, University of Michigan, 1994.

For contemporary wine scams (should the link disappear), see Bianca Bosker, “A true-crime documentary about the con that shook the world of wine.” The New Yorker, October 14, 2016.